An opening statement prepared for the RESAW25 conference, 5-6 June, University of Siegen, Germany.

A History of Researching the Datafied Web

It’s a real pleasure to return to the RESAW conference, and to Siegen. We were asked to contemplate a deceptively simple question: how did the web become datafied?

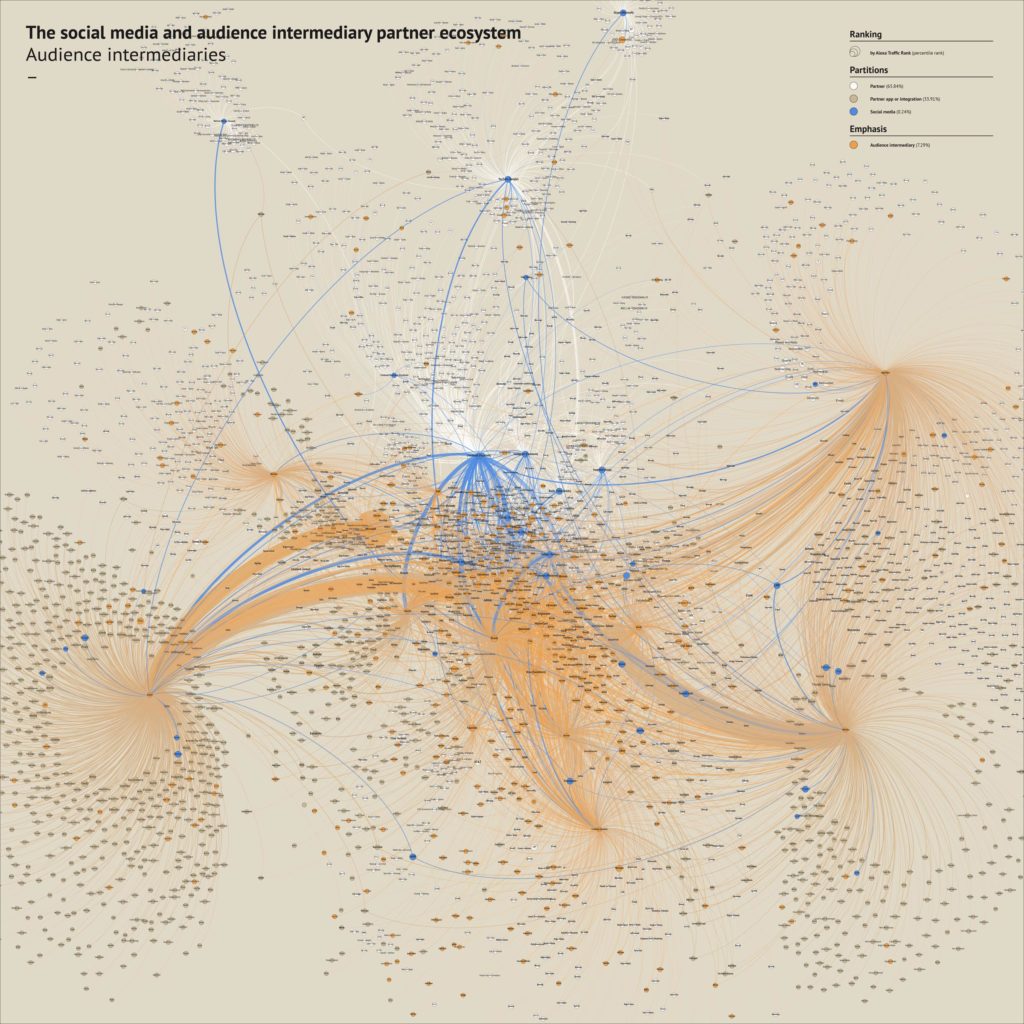

To begin, we should ask: what do we mean by the datafied web? Drawing on the work I’ll present this afternoon with Fernando van der Vlist, we understand it as an evolving ecosystem where data collection, analysis, and monetization are central to its operations (van der Vlist and Helmond, 2021; Helmond and van der Vlist, 2023). For better or worse, digital advertising underpins most of the web and app ecosystem– through often invisible mechanisms of tracking and targeting.

Today, we will argue and show that the datafied web is a vast, complex ecosystem of interconnected platforms, intermediaries, and advertising technologies, many operating seamlessly in the back-end. Some actors are linked in long chains, each offering part of the services or infrastructure needed for targeted advertising. Others—like Google—have built fully integrated ad stacks, serving all sides of the market, which has resulted in a now highly-contested monopoly power.

To understand how this came to be, we need to trace the actors, tools, techniques, and infrastructures that enabled it—and crucially, the purposes for which they were built. On the front-end, we’ve seen increasing datafication through metrics like likes, shares, and retweets. But on the back-end, we’ve seen the rise of programmatic advertising, tracking and targeting techniques such as cookies and header-bidding, data broker networks, and opaque data infrastructures that underpin a billion-dollar industry centered around audience data—which we’ll talk more about this afternoon.

Central to this transformation were APIs, which, as Tim O’Reilly (2004) once framed it in the era of Web 2.0, turned the web into a programmable interface. APIs expose website data and enable websites and platforms to talk to each other and exchange data and functionalities. APIs are central to the platformisation of the web, enabling platforms to technically weave themselves into new domains (Helmond, 2015). They interconnect platforms and now function as the material pipelines of the datafied web.

But how do we study this vast, layered, and often invisible ecosystem in the back-end?

Here, I want to make a case for the continued relevance of web archives and the humble hyperlink as analytical objects, even as the web increasingly shifts from open websites to mobile apps and AI-driven interfaces.

Hyperlinks may seem mundane, but they are incredibly rich. They are highly standardized, yet diverse in their use. They can carry data flows—for example, through short URLs (see Helmond, 2013) or campaign parameters. They can function as API calls, connecting websites to other platforms and databases. And they can point us to the broader ecosystem of actors and data infrastructures in which a website is embedded.

In my very first paper, with Esther Weltevrede, we used Internet Archive data to reconstruct historical hyperlink networks to map the evolution of the Dutch blogosphere (2012). We showed its decline and the growing presence of social media. But one striking finding was the abundance of web counters in the early blogosphere—bloggers weren’t just sharing content, they were proudly displaying visitor stats. It signaled an early culture of measurement in the datafied web.

Later, with Carolin Gerlitz, we examined how social media platforms introduced Like and sharing plugins. These tools didn’t just show popularity—they also enabled tracking. They linked websites to the platform, pinging back user data and building what we called a “data-intensive infrastructure” supporting the commercial surveillance complex (Gerlitz and Helmond, 2013).

This led me to develop what I later called historical source code analysis—an approach to studying archived HTML not for its content or visual design, but to reconstruct the data infrastructures behind websites: counters, trackers, third-party scripts. I see it as a way to study website ecologies, revealing the broader data ecosystem of the web from the vantage point of a single site (Helmond, 2017).

So even as we move away from the open web, web archives remain valuable. They let us reconstruct the political economy of datafication: how advertising technologies, analytics tools, and platform integrations have evolved and have reshaped the web’s infrastructure.

Because while the front-end of the web has changed dramatically, the back-end has undergone a deeper transformation: from simple counters and cookies to complex stacked infrastructures designed for the capture, circulation, and commodification of data.

So let’s use this week to ask: how did the web become datafied? Who built it that way and for which purposes? And how can we use the tools of web historiography—web archives, archived source code, and hyperlink networks—to tell that story?

References

Gerlitz, Carolin, and Anne Helmond. “The Like Economy: Social Buttons and the Data-Intensive Web.” New Media & Society, vol. 15, no. 8, Nov. 2013, pp. 1348–65. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444812472322.

Helmond, Anne. “Historical Website Ecology. Analyzing Past States of the Web Using Archived Source Code.” Web 25: Histories from the First 25 Years of the World Wide Web, edited by Niels Brügger, Peter Lang Publishing, 2017, pp. 139–55, https://hdl.handle.net/11245.1/8e8618c9-1a47-438b-89d0-f637501e434e.

Helmond, Anne. “The Algorithmization of the Hyperlink.” Computational Culture, no. 3, Nov. 2013, http://computationalculture.net/article/the-algorithmization-of-the-hyperlink.

Helmond, Anne. “The Platformization of the Web: Making Web Data Platform Ready.” Social Media + Society, vol. 1, no. 2, Jan. 2015, pp. 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305115603080.

Helmond, Anne, and Fernando van der Vlist. “Situating the Marketization of Data.” Situating Data: Inquiries in Algorithmic Culture, edited by Karin van Es and Nanna Verhoeff, Amsterdam University Press, 2023, pp. 279–86, https://doi.org/10.5117/9789463722971_ch17.

van der Vlist, Fernando N., and Anne Helmond. “How Partners Mediate Platform Power: Mapping Business and Data Partnerships in the Social Media Ecosystem.” Big Data & Society, vol. 8, no. 1, Jan. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/20539517211025061.

Weltevrede, Esther, and Anne Helmond. “Where Do Bloggers Blog? Platform Transitions within the Historical Dutch Blogosphere.” First Monday, vol. 17, no. 2, Feb. 2012. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v17i2.3775.